Viewing the painting = Reliving that Moment

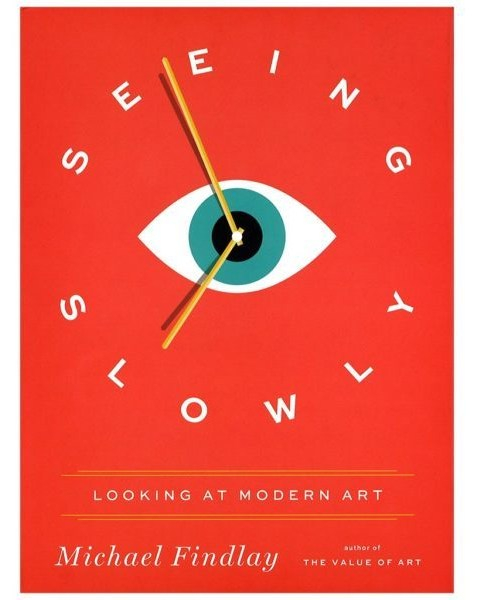

Currently in Europe; Studio Italia has ended, about to start Atelier Provence. One of our blog subscribers, a docent at the National Gallery of Canada, recently finished reading Michael Findlay’s Seeing Slowly; Looking at Modern Art (Prestel Publishing, 2017), and noticed that there was maybe a link between what he had just read and our recent post on time. He proposed us this text, and we said “why not” since it deals exactly what we try to do at Walk the Arts, letting go in plein air painting through authenticity. Of course, the text is indeed interesting. After an stimulating exchange, here is the final text. Thank you and to you, Robert Sauvé.

Currently in Europe; Studio Italia has ended, about to start Atelier Provence. One of our blog subscribers, a docent at the National Gallery of Canada, recently finished reading Michael Findlay’s Seeing Slowly; Looking at Modern Art (Prestel Publishing, 2017), and noticed that there was maybe a link between what he had just read and our recent post on time. He proposed us this text, and we said “why not” since it deals exactly what we try to do at Walk the Arts, letting go in plein air painting through authenticity. Of course, the text is indeed interesting. After an stimulating exchange, here is the final text. Thank you and to you, Robert Sauvé.

Here’s a curious paradox: stopping time by painting quickly. Can one set a trap to catch the moment’s impression? Can the artist’s canvas trap the beauty and the wonder of observed events which melt all too quickly in the flow of time? Can time be halted? Yes, says Michael Findlay, obviously, this is what artists do. So too, the viewing of art requires “halting” the flow of time. This is the key idea of Michael Findlay’s reflections in his latest book on art appreciation. Time seems to stand still for viewers who dwell on works of art in a slow and measured way (i.e. longer than the average ten or so seconds per painting that galleries have measured as the visitor viewing time). Only then can a different and more personal viewing experience emerges. It takes time to appreciate the ‘plein air’ artist’s mission to grab that moment. The authenticity of the artist’s “capture” slowly emerges as one’s eyes, feelings and imagination dwell on a work of art. It takes time for the viewing of art to become an art viewing event; such an event is the gold standard of a successful art gallery visit.

The impressionist’s spontaneous painterly reaction suggests that his work is quickly done with the goal of holding still a view of the moment. Getting the sun, the shade, the light … in a word, getting nature’s mood just right at that moment. No time to lose. At any moment one risks losing that mood. Skill, technique and confidence are key, but so is spontaneity … and speed. And for this to occur one has to fully let go, even to forget who he or she is. One has to be in the moment to get it on the canvas as quickly as possible. We know, for example, from artists such as Monet and Pissarro that in any one morning many such grabs were done — as the sun moved, as shadows shortened, as clouds drifted in. Monet’s Rouen’s Cathedrals or the Gare Saint-Lazare series give witness to this compelling attraction for the moment. For the Impressionists the goal was not so much to generate a series of paintings as it was to get the feel of the moment just right, to be authentic; their main objective was to trap an ephemeral ‘impression’, to grab the moment, to grab the uniqueness of “that’ moment, a painterly carpe diem.

What the artist does in one manner (i.e. by quickly capturing an ephemeral perception) is mirrored differently by the art viewer (i.e. a more leisurely focus enables the welling up of the mood of the moment captured by the artist). In this way, the beholder who slows their viewing time can “grab that moment” as well. They would be able to appreciate the impressionist’s skill and confident execution by simply reversing the process – by letting the spirit of the artist’s capture emerge in its own good time. This takes time. Findlay tells the story of a young girl preferring to sit at the centre of an Impressionist exhibition explaining that she would rather let the colours come to her rather than her go to the colours. Later she would gravitate to the paintings that sparked added interest. But first she was taking her time, letting the pictures, the images, the stories, the colours come to her. She put aside all the prior agreements of how art viewing should be done.

For Findlay, art viewing ought not be an exercise of sorting visual experiences based on art-viewing conventions. Rather, we have to set aside frameworks of interpretation. And for that to occur, we must believe in ourselves; we must tame whatever feelings of vulnerability that can arise when setting aside the security blanket of frameworks of understanding. Letting go to let-in the work of art is also an acquired habit… and that too takes time! “We don’t see things as they are, we see them as we are,” Anaïs Nin writes (Findlay’s book p. 52). As we gaze at works of art, we are also gazing within ourselves.

Findlay’s Seeing Slowly is an important reflection. It is also a rewarding read for those who want to have a full and rewarding art experience. The spontaneous paintings of plain air artists and the slow viewing of gallery visitors complement each other. In their ways, each strives to be ‘in the moment’. And for the art viewer, that ‘moment’ is the threshold where the labyrinthine adventure begins — slow art viewing and self-exploration go hand in hand. (Robert Sauvé)

Well this well timed as I am about to step into that world of “exhibiting” my work. I have asked myself the standard questions of why am I doing this….what do I expect to achieve? I would hope that at least one of my paintings has that pull that stops people just walking on by. I thought that I had grown a thicker skin; able to handle critiquing of my work, even negative feedback, without getting stressed….but to put my work up for others to view formally is, in my mind, a whole new concept.

Have had same thoughts and feelings and self doubt … I started out at my mother’s kitchen table – Mother was an artist (trained by nuns) and was a thorough teacher – in the 1950s – with 5 children and no money … I have been an artist for 60 years and these questions seem to be part of the psyche … just carry on Once in awhile faith returns and smiles